Discover more from Creative Leadership

Do you remember your first experience?

For me, it was on the Sacramento River during the summer of 1970. I remember, as if it was yesterday, the hulking and eerie “ghost fleet” moored in Suisun Bay as our family’s rented houseboat floated by. While the size of the fleet has diminished over time to only a few dozen waiting for the scrapyard, to my young eyes there must have been thousands of ships. And while I now know it was primarily a merchant reserve fleet, I knew without a doubt as a boy that these vessels were battleships involved in the most dramatic battles of World War II. It was an unforgettable moment.

Another memorable experience was the first time I stepped into a fully themed attraction queue. I had grown up playing and working at Lagoon, an amusement park in Utah, but its rides were so generic they actually called the park’s wooden roller coaster, The Roller Coaster. Its Ferris wheel was called The Ferris Wheel and its sky ride taking riders over its midway was called, yep, The Sky Ride. There was no theming at Lagoon unless you count a Pioneer Village they added in the 1970s. However, the log flume in this Pioneer Village was called, you guessed it, The Log Flume. So in the summer of 1991 when I first stepped into the thick forest inside the brand new E.T. Adventure at Universal Studios Hollywood, I felt transported to a different place and time. For me, the immersive theming allowed me to trust my senses and enjoy the illusion. Deep down, I knew I was on a Hollywood backlot, but I didn’t care. I trusted that I was in a forest.

Next, it was the time I took my children to LEGOLAND California. It was 1999 and the park had just opened. As you might expect, we explored Miniland USA, rode the Vekoma Dragon coaster and enjoyed playing with the ubiquitous bricks. However, it was The Driving School that my kids loved the most. And sure, they enjoyed hopping in the little self-propelled LEGO cars, but it was the safety briefing beforehand that made them feel special. The briefing on how to operate the vehicles and the rules of the road was invaluable, but it was the “license” that made them feel special. It was such a small thing, but LEGOLAND turned what was essentially a safety briefing with valuable information we needed in order to move forward on the attraction into a magical moment for our family.

Then there was September 1989 when I sat down within the great rotunda inside the now torn down North Visitor Center on Temple Square in Salt Lake City. With over 5 million annual visitors, this is the No. 1 tourist attraction in Utah. More people walked through its exhibits, stepped inside its theaters, listened to the Tabernacle Choir and researched their family history than explored Zions National Park, Moab or even visited the Wasatch Range of the Rocky Mountains. The signature attraction in the visitor center was a giant spherical mural of the universe surrounding an 11-foot tall replica of The Christus, a 19th Century sculpture of Jesus Christ by Dutch artist Bertel Thorvaldsen. As I sat among the planets and stars and looked at the outstretched hands of Jesus after returning home from my own two-year mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I internalized His words like never before. I could feel that our Earth, this universe and my own life were part of a much bigger plan.

And finally, a visit to Hogwarts at Universal Studios shortly after it opened in 2010. Our family spent over $80 on Butter Beer, my children spoke with an English accent for five straight hours and we each left with $50 wands that probably cost .50 cents to make in an overseas factory. But it was the debate we had while standing in the exit retail store after riding Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey that we still talk about. Yeah, yeah, we know it was the ubiquitous “exit through retail.” Universal’s goal, no doubt, was to get us to act on our feelings and buy something. However, the exit experience, theming and merchandise placed us inside the story. As we stood in front of Quidditch jerseys, the debate wasn’t about whether $70 was too much for what was essentially a rugby jersey, but which house we belonged in. For the record, my wife and youngest daughter are in Gryffindor. My son is a Ravenclaw. My oldest daughter is Hufflepuff. And sadly, yes, I’m a Slytherin. “Go Green!”

What all of these memories have in common is that they are connected to bigger stories. First, World War II and the epic battle between good and evil that defined the 20th Century. Second, the story about an alien lost on planet Earth, which also happened to surpass Star Wars as the highest-grossing film of all time in 1983. Third, teaching your children to drive is always a fun and humorous story. Fourth, an authentic spiritual experience connected to what Hollywood once called The Greatest Story Ever Told. And fifth, the story of “the boy who lived” and his magical world.

All of these experiences are connected to great stories, but great storytelling is not what this post is about. What this post is about is how to bring any story to life through experiences.

And over the course of 40 years working in theme parks, museums, brand experiences and big spectacular events, we’ve found there is a formula. There is a model. A secret sauce. One of my favorite designers would even call it “awesome-sauce.”

It’s how any story can translate into an experience.

Every time you walk into a theme park, museum, visitor center, factory tour, exhibit or attraction, you are stepping into an experience. I believe those that follow this model religiously are more memorable than those that do not.

For me, the first time I overtly recognized this model was in 2004 when working as the creative director on the Honeywell Technology Experience. Located in Washington, D.C., Roll Call called this corporate visitor center an “EPCOT-style vision” and a “dramatic leap forward in the…scramble to make standout connections.”

At the time, I worked at a company called The Brand Experience and we had partnered with architect Richard Zampi and Lynch Exhibits on the creation of this brand experience for Honeywell. The story was all about showing guests that this big multinational corporation is “building a world that’s safer and more secure, more comfortable and energy efficient, and more innovative and productive because its people and its customers have a passion and purpose. From the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter to equipping an old petrol chemical plant with new sensors, Honeywell and its customers create technological stuff that matters.”

But the challenge was how we would bring this story to life?

First, we started with an iconic globe to show that this is a global story. Second, we created a queue featuring the people of Honeywell and their passion for working on stuff that matters. Third, we led guests into a theater that acted as a pre-show for the main experience. Inside the theater, we shared a “Day in the Life” of Honeywell from the sun coming up in the morning to the moon setting at night. Fourth, this theater led to a series of interactive experiences and exhibits where guests could learn more about Honeywell’s story. And fifth, we created a series of high-end conference rooms off an impressive lobby where guests could gather to talk more about Honeywell and even buy their services.

As we created this experience we began to realize that it followed a model common in theme park attractions around the world. So, we called it “The Theme Park Model.”

Icon: The symbol of our story and something that draws guests in.

Queue: This is where guests take their first steps into the story so we must introduce them into the story thoughtfully.

Pre-show: The story is usually presented in a more formal way, like an orientation. To put it another way, this is often the place where you tell guests what they are about to experience.

Main Attraction: This is why guests are coming and is the heart of the experience where the story is brought to life in its fullest.

Exit Through Retail: And finally, guests exit through some type of retail experience on their way out where they are challenged to take a piece of the story with them.

One of our biggest challenges in the early days of using this model with our corporate clients was to convince them not to take everything so literally. The icon could be as simple as how the lobby was designed rather than some big iconic element you’d see at Disneyland. The queue was more about emotion, making a solid first impression and building trust than actually making people wait in line. The same goes with the pre-show as this could be as simple as a large graphic or video monitor on a wall or as immersive as 4D theater. The main attraction isn’t a ride but the reason why people are coming to visit. For some clients, it was a product demo or factory tour while for others it was the briefing itself. And finally, it’s not often guests will ever exit through a real retail store in a corporate environment, but brands create these experiences to sell something. Sometimes that “sell” might come in a conference room, huddle space or even while drinking a cup of coffee.

Even though I often clumsily clung to the carnival vernacular of the themed entertainment industry I grew up in, this model always worked because it is so ingrained in psychology, culture and history. You can find examples of it in a variety of experiences and stories—from the original Tabernacle in the Wilderness described in the Old Testament to the latest attractions at Disney or Universal Studios. If you’ve ever felt confused or disjointed inside an experience, it’s usually because the designers, architects and storytellers have ignored The Experience Model.

While we don’t claim to have invented this model, we will take credit for adopting it, synthesizing it, evangelizing it and applying it to experiences and attractions around the world. In fact, after that initial “aha moment” with Honeywell in 2004, we continued using this model in projects like the Polycom Executive Briefing Center in 2007, Nakheel’s sales centers in Dubai in 2008, the Lockheed Martin Space Experience Center in 2010 and a variety of other projects.

In 2013, I was working as Executive Creative Director at The Brand Experience and we hired White Design to help us design the experiences inside the new corporate headquarters for 84.51° in downtown Cincinnati. After briefing Peter White and his designer Thomas Dangerfield on our ideas using The Theme Park Model, they came back with a presentation where Thomas compared our model to something he had developed called “The Human Communication Model.” He connected our icon to his concept of attract. He compared what happens inside the queue to building trust. While we talked about the pre-show being a place of orientation, he compared it to delivering information. The main attraction, he said, was a place where the story is internalized. We agreed. And finally, he described the exit-through-retail experience as a place where we want guests to act. So true.

We loved his insights so much that we actually hired Thomas as the company’s new associate creative director. We continued to collaborate on a variety of projects for the short time he worked with us. During this time, The Theme Park Model and Human Communication Model merged together and evolved with the input of others. In addition to Thomas Dangerfield and White Design, it’s probably impossible to give credit to everyone who had a voice in developing this model, but a few key people stand out. First, the CEO and Founder of The Brand Experience, Dale Tesmond, who supported me when I first told him I wanted to talk about theme parks with Honeywell, IBM, Lockheed Martin, Polycom and other corporations. Second, architect Richard Zampi who listened to us and offered valuable feedback when we talked about shaping the architecture around this model. Third, Andrew Peters, the creative director who replaced Thomas at The Brand Experience. He worked with a young freelance graphic designer named Brent McDowell to better visualize and articulate these models. And fourth, Shawn McCoy at JRA who, as a client and former colleague, offered valuable insights as we continued to use these models to shape experiences on projects like the American Airlines Museum and Qasr Al Watan Presidential Palace in Abu Dhabi.

When I launched my own company in 2017, we decided to combine both models into one that we simply called The Experience Model. It’s now part of every project and every experience we work on, from the FM Global Centre in Singapore to Ozark Mill in Missouri.

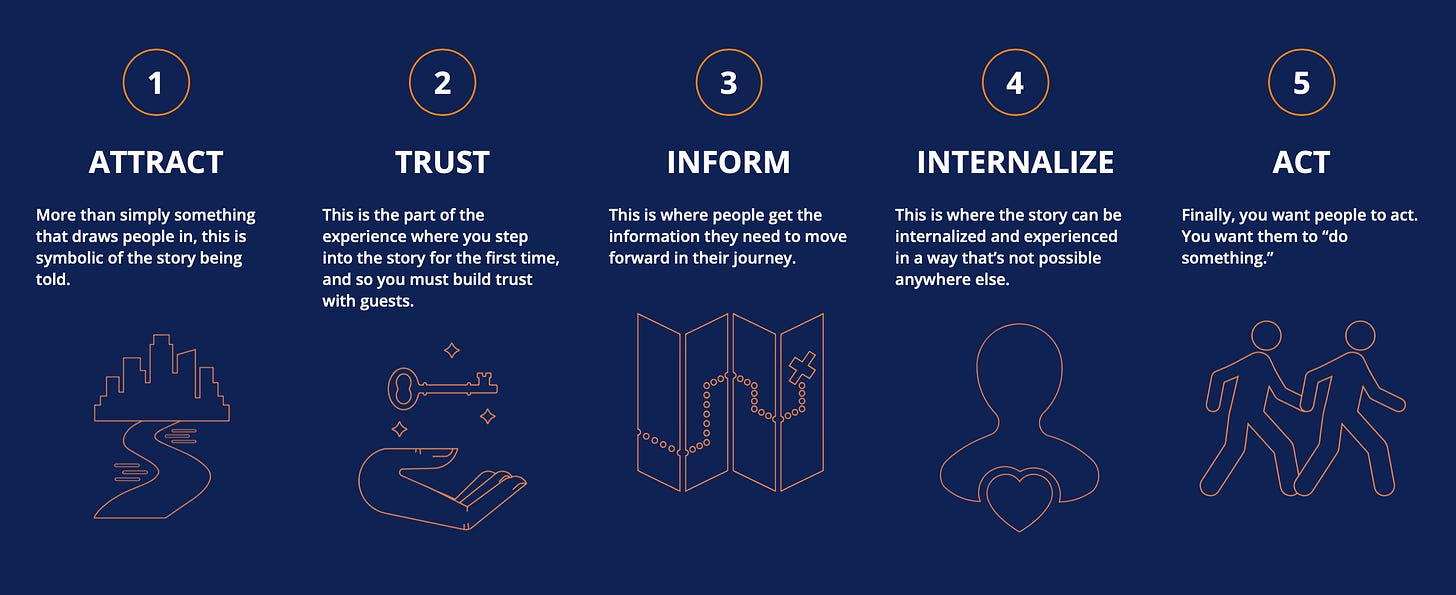

The model can be explained in five parts:

Attract: All great experiences feature an iconic element designed to attract people’s attention. More than simply something that draws attention, it is symbolic of the story being told.

Trust: In other words, how do we gain trust with the audience? This is the part of the experience where you physically step into the story for the first time, and so it’s important that that first step begins with trust.

Inform: Before moving on, visitors need to be briefed. They need information. This is usually a pause in the experience where you “tell them what you’re going to tell them.” It’s an overview of the story and often provides some orientation on what’s going to happen next.

Internalize: This captures the reason why people are visiting the attraction. It’s the main attraction where the story can be internalized and experienced in a way that’s not possible anywhere else.

Act: Finally, you want people to act. In many attractions, this can be the ubiquitous “exit through retail.” It can be natural to purchase a shirt declaring our 6-year-old was brave enough to ride Expedition Everest at Disney World. However, the real goal should be something deeper. Hopefully, you want people to become part of the story and feel an emotion that will inspire them to act. The best and most memorable attractions feature an exit experience that goes far beyond something so commercial.

If I could give credit to the one original creator of The Experience Model, I would, but perhaps it’s something that is just so ingrained in human psychology that it’s impossible to define when it was first invented. In fact, Adam Berger, an independent writer in the theme park industry who we’ve worked with before, reminded us that perhaps this model is actually just another iteration of The Hero’s Journey presented by Joseph Campbell.

In The Hero’s Journey, you first have to ATTRACT the Hero’s attention, then find a way to build TRUST with that hero before he or she is given the INFORMATION they need, usually by a mentor of some sort, to move forward in their journey. At some point, the hero faces a challenge where what they have to learn is INTERNALIZED. They then ACT and either meet success or failure.

The Experience Model works because it is not just a way to translate a story into an experience but a way stories have been told for centuries. And there’s a reason for this—it’s because it works. “Whether it’s The Hero’s Journey or The Experience Model, no one truly invented these things,” Adam said. “The human psyche created the model and we just molded the shape of our stories and experiences around that model. It’s the archetype.”

An earlier vision of this post was published on LinkedIn in 2018.

Great article Geoff!