Discover more from Creative Leadership

Lessons From Lagoon’s David W. Freed

One of America's Last and Largest Family-owned Theme Parks Loses its Leader

“Meet Dave in front of the Log Flume. Meet Dave in front of the Log Flume!”

It was the summer of 1985 and these words crackling over my Motorola Pager strapped to my belt always put fear in me. No matter where I was in Lagoon’s Pioneer Village, I’d dash as fast as possible to the Log Flume to meet David W. Freed, the Lagoon executive who oversaw the Rides Department and, eventually, everything else at Lagoon.

Dave died at the age of 74 last week.

As the family announced in his obituary, he “passed away peacefully at home surrounded by family on Christmas Eve, December 24, 2022.” His death comes just over two years after his father Peter Freed died at the age of 99. Lagoon is one of the last and largest family-owned theme parks in the United States and Peter and his oldest son David were its leaders. As the Freed family wrote, “Dave's absence in the lives of those who knew him leaves a deep void.”

As I grew up a short bike ride from Lagoon in Farmington, Utah and started working there when I was 14, I first met Dave Freed when I was a clean-up boy and lifeguard at Lagoon’s famous and now replaced by a waterpark million-gallon swimming pool. I then spent one year as an area supervisor in his Rides Department before moving to the Entertainment Department to work as a stage manager for the park’s 100 performers and six shows. Through my formative years of high school and college, I worked 10 seasons at Lagoon. It’s where I got my start in what we today call the “experience industry.”

The last time I talked to Dave was 2003 when I was writing an article about his father Peter for FUN WORLD magazine. I saw Dave’s sister Kristen, who worked side-by-side with Dave at the park, when I visited Lagoon in the spring of 2021 to speak to 250 of its front-line managers about a career in the themed entertainment industry. And I briefly met his daughter Julie at an industry conference in November 2021. What I’m trying to say is that I only knew Dave and his family from afar. However, when I got the news that Dave died, it left me thinking about the lessons I learned working for him as a teenager 40 years ago that still influence me today.

HARD WORK PAYS: The first time I really saw Dave Freed I was a 15-year-old clean-up boy at Lagoon’s swimming pool and looking up at him from inside the aging pool’s filter house. He was standing up on the concrete floor and I was down in the filter pits with another clean-up boy trying to remove and clean each of the mesh covers surrounding hundreds of tubular filters. It was a dirty job and urgent because we were having a hard time keeping the pool running efficiently 50 years after it opened in 1932. The swimming pool, which was located in the center of the park, was a classic. The deep end featured Utah’s only outdoor diving platform and three diving boards. The swimming pool’s huge steel waterslide was located smack dab in the middle of the water. People would climb thirty feet straight up its ladder to descend down its steep pitch. Running water and regular waxing by clean-up boys like me kept its shiny steel surface smooth and fast. The cinder block pool house, locker rooms and food stand all had multiple coats of the same aqua blue paint. A beautifully landscaped sunbathing green snaked around half of the pool. The same sign that was installed decades before still hung over the turnstiles, welcoming all who entered. This sign heralded a pledge that guests could “SWIM IN WATER FIT TO DRINK.” To keep that hilarious promise from another era of advertising, I found myself as a teenager scraping muck from the swimming pool’s filters for hours on end. Dave was looking over the work at about four hours into the project. After seeing how hard we were working in less-than-ideal conditions, he whispered something to our area supervisor Rhonda Powell, she nodded and smiled and then as soon as Dave had walked out, Rhonda told us that Dave was so impressed with our hard work that he was going to pay us double our usual $2.50 an hour wage for the day’s work. Now that might not seem like a lot today, but to a young teenager in his first real job, I learned quickly at Lagoon that hard work would be recognized and rewarded. One year later when I turned 16 and was now a lifeguard at the swimming pool, Dave returned yet again to be there when Rhonda pinned on my gold badge. These shiny gold badges were pinned on employees who earned the coveted “Golden Gopher Award.” Every week, a few of the more than a thousand seasonal employees at the park were singled out for their hard work. When Rhonda pinned the badge on my shirt, Dave Freed was there to shake my hand. As a teenager, I was in awe that such a high-ranking executive would take time out of his busy schedule to personally thank me.

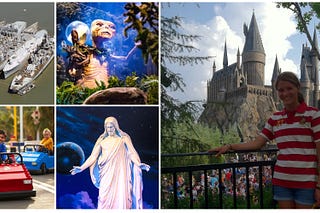

DRESS FOR SUCCESS: Part of that awe, no doubt, came from the fact that Dave Freed himself dressed for success. He was cool and confident as he strode the park in Levi 501s, a knit tie and aviator sunglasses. The picture with this article says it all and that is the Dave Freed that I knew. College educated, handsome, and smart. He drove the latest Porsche 911 convertible, dressed straight out of GQ and spent his vacations on safari in Africa with his wife. When I was assigned to help source the uniforms for the area supervisors after being promoted to one, Dave introduced me and another supervisor to the store in Salt Lake City where he wanted us to purchase the hundreds of golf shirts that would be required over the long hot summer. When I walked in, I entered a world of fashion I didn’t know existed. You see, as one of eleven children in the then mostly rural Farmington, my fashion choices usually involved wearing clothing handed down from my older brothers. Splurging on high fashion in the Thatcher family usually involved JC Penny. However, buying high-priced fashion wasn't the lesson I learned from Dave Freed. No, it was that appearance matters. He obsessed over little details like ensuring supervisors always looked professional. The notes he gave us as he walked the park every day mostly dealt with cleaning a mess or repairing something that looked amiss. To our great chagrin, he wanted the lifeguards wearing shirts so we’d look more professional. We complained to Rhonda about that last fashion edict a lot because we felt our job as a lifeguard was to get a tan. Later, when I was a new area supervisor, I was walking out of the Rides Department office when Dave yelled over to me from his Porsche, “Come over here Thatcher.” I obeyed and quickly jogged to his beautiful car. “Hop in,” he said, “I need your help to wash my car before dropping it off for service at the shop.” On our way over to the car wash in downtown Farmington, Dave explained why the job was important. “I’m going to teach you a lesson, Geoff, never take a dirty car in for service. If the mechanics think you don’t care about your car, they won’t care about it either.” More than 20 years later, I saw Dave and his sister Kristen walking the floor at the annual Expo of the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions. He was wearing a suit and tie. It was yet another reminder of that lesson as a teenager. If you want people to take you seriously, dress the part.

FUN IS SERIOUS BUSINESS: There was a reason why we feared getting paged to meet Dave and a reason why we ran. Dave Freed was a tough boss. He was serious. He didn’t laugh with you and slap you on the back—or at least he didn’t with me. I’ll be honest, there were times as a teenager when this frustrated me. There’s a reason why I only lasted one year as an area supervisor in his Rides Department. My 1985 midseason review with Dave was brutally honest and left my young ego battered and bruised. In hindsight, Dave was right, of course. I shouldn’t have argued with him over whether we should add more boats to the Log Flume, and I shouldn’t have swam after hours with the lifeguards. The older I got the more I realized why Dave was so tough. The job of fun is serious business. In the 1980s, the rides were often operated at regional parks by teenagers. In my final season at the swimming pool, I also worked as a train engineer. I was 17 years old and Lagoon was entrusting me to operate a 24 inch gauge steam engine fired by a propane flame. Running a steam engine required controlling the boiler pressure, water level and speed of the train all at the same time. The engineer had to keep one hand on the throttle while adjusting knobs, levers and other mechanisms that controlled everything from the burner to the water level. In the rear-view mirror, you kept your eye on the guests. The most important job of the engineer was to inject water into the boiler on every trip. As we were taught during our training, “If you let that water level dip too low, the engine could explode!” We were teenagers managing teenagers. Perhaps injecting a little fear—and respect—into all of us running these rides wasn’t a bad thing. One time, Dave even played the Rolling Stones’ “Under My Thumb” while all of us were busy taking our management training tests during the off season. As the song played, Dave just stood in the corner watching. Yes, he was tough. However, I learned much later in my career that this toughness went far beyond training teenagers to take their job seriously. Several years ago at the annual IAAPA Expo, I bumped into Boyd F. Jensen II. Boyd’s father had worked with Dave at Lagoon for decades and he had worked there himself as a teenager. Boyd is now a prominent attorney in the industry defending parks against litigation. He is, according to an honor given him by IAAPA, an “industry advocate involved in government relations as well as safety, maintenance and standards development, penning articles regarding such topics as ride G-forces and biomechanical effects.” As we talked about working at Lagoon as teenagers, I joked with Boyd about Dave’s legendary toughness. Boyd grabbed my arm and said, “He’s tough for a reason. You have no idea how much work he’s done behind the scenes to keep our industry safe.” Boyd went on to describe how Dave ruffled feathers and fought to establish industry safety standards. “Few people know about the important work he’s done,” he said. I certainly didn’t until Boyd shared the stories with me.

SELF-AWARENESS: This lesson came from the last time I talked with Dave Freed 20 years ago when I was writing that article about his father Peter. Everyone I talked with described Peter the way I too remembered him when I worked at Lagoon as a young man: “Kind, gentle, calm, forgiving…” The words “tough” was never mentioned. When I called Dave to talk with him about his father Peter, he said something that surprised me. “My dad is my role model.” Perhaps remembering that tough management review I had received as a teenager, I instinctively blurted out over the phone, “Really?!?!?!?” I then collected my thoughts and said, “But Dave, your management style is so much different than your fathers.” Dave then paused, and I got to hear the authentic emotion in his voice as he described his own leadership through the eyes of his father. “Don’t you think I know I’m not my dad? Yes, I’m afraid I haven’t learned from him as well as I could,” Dave confessed. “People may not believe me, but I honestly want to be more like him.” This kind of self-awareness left me speechless. Dave’s honesty still makes me wonder if I can have that same kind of self-awareness of my own weaknesses. The last thing Dave said to me about his father in that interview was simply this: “He is my hero.”

Hero.

One could argue that the best compliment a child could ever give their father is to simply call him their hero.

As the dictionary defines it, “a person who is admired” with “outstanding achievements” and “noble qualities.” Even sometimes “superhuman qualities.”

And so that word “hero” now echoes across time as Dave’s daughter Julie posted a tribute to him on Instagram announcing the birth of Dave’s first grandchild on December 27th, just three days after his death.

In the post, she simply called Dave “My Father & Hero.”

Perhaps being a hero to your children is the final lesson that David W. Freed can teach the thousands of teenagers who worked at Lagoon over the decades.

Subscribe to Creative Leadership

Geoff Thatcher and the family at Creative Principals writing on the subject of creative leadership in work and life.

Very nice story and tribute Geoff! Thank you!